Let’s talk about your placenta and the umbilical cord!

The placenta is a pancaked-shaped organ that develops during pregnancy and is attached to the uterine wall. It provides oxygen, blood, and nutrients to your growing baby while also eliminating waste products.

Baby is connected to the placenta via the umbilical cord – a flexible cord of tissue that brings oxygen, blood, and nutrients from mama to baby.

In this article, you will learn all about the placenta, potential complications, how it’s expelled, and more! We’re also going to cover umbilical cords so that you understand what’s normal and what’s not with baby’s cord, too.

Follow @mommy.labornurse on Instagram to join our community of over 650k for education, tips, and solidarity on all things pregnancy, birth, and postpartum!

What is the placenta?

The placenta is a pancake-shaped organ that your body grows during pregnancy. It’s located in your uterus and attaches to your growing baby via the umbilical cord. The placenta is what’s responsible for providing baby with everything they need while in utero!

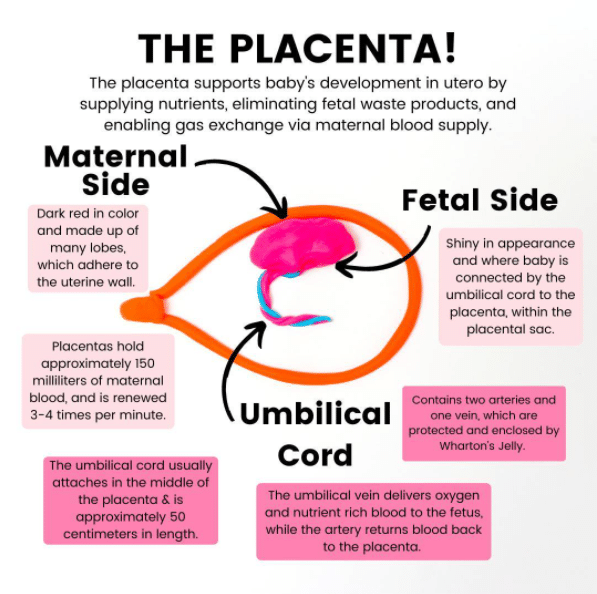

The placenta does this by supplying nutrients, eliminating fetal waste products, and enabling gas exchange via the maternal blood supply. It’s one of the only “disposable” organs because once your body is done using it, it gets expelled! A new placenta is grown for every pregnancy.

Your placenta has two sides:

- Maternal side: This side is dark red in color and made up of many lobes which adhere to the uterine wall

- Fetal side: This side is shiny in appearance and is where baby is connected by the umbilical cord to the placenta within the placental sac

Your placenta holds approximately 150 mL of maternal blood that is renewed 3-4 times per minute!

When does the placenta form?

The placenta starts forming very soon after your fertilized egg implants in the uterus, and it almost immediately starts secreting the hormone hCG. But it takes until between weeks 10 and 12 for it to be fully functioning and take over providing for your growing baby.

This is a big reason why the first trimester is often so exhausting and nausea-inducing! Developing the placenta takes a lot of energy, and until it fully takes over the production of a lot of other crucial hormones to sustain pregnancy (including progesterone), your body is working in overdrive.

This all explains why the second trimester often comes with a boost of energy and diminishing first trimester symptoms.

One important thing to note is that the placenta continues to grow for the entirety of your pregnancy. It’s usually fully mature around week 34 and has a final weight of about 1 pound (source).

Placentas in twin pregnancies

- Dichorionic diamniotic (Di-di) twins have two amniotic sacs and two placentas and can be either fraternal or identical. Di-di twins usually have the lowest risk of complications because the babies have their own amniotic sac and their own placenta. The placentas can either be fused or separate in a di-di pregnancy

- Monochorionic diamniotic (Mo-di) twins can only be identical. These babies share one placenta but have two amniotic sacs. Due to having a shared blood supply, they are at an increased risk for certain complications

- Monochorionic monoamniotic (Mo-mo) twins are at the highest risk for complications because they share one placenta and one amniotic sac. These twins, which can only be identical, are the rarest kind of twins

Where is the placenta located?

The three most common spots for your placenta are:

- Fundal placenta: This is thought to be the most common placental location. A fundal placenta is located at the top of your uterus (aka your fundus!), and often is classified as posterior fundal or anterior fundal depending on if its more towards the back or front

- Posterior placenta: This is when your placenta is located at the back of your uterus, against your own back! Some say that posterior placentas mean that you will feel the most movement from baby, and it may allow baby to get in the optimal position for birth most easily

- Anterior placenta: This is when your placenta attaches to the front wall of your uterus. In this position it can be harder to feel baby move initially because there is a placenta “cushion” in the way

All three of these are normal places for your placenta to develop and do not pose any risk to a vaginal delivery!

Placenta previa

View this post on Instagram

A placenta previa is when your placenta covers your cervical opening. When you have a previa you cannot have a vaginal delivery because the placenta is in the way, and it can be dangerous for your uterus to contract with your placenta that close to your cervix!

Previas are graded, and here are the different ways we describe them:

- Partial previa: Your placenta is partially covering the cervix, in this case it is much more likely to move during your pregnancy, and comes with less potential complications

- Complete previa: Your placenta is completely covering your cervix. In this case, it’s much more likely to stay put, but it’s still possible to move before you are 37 weeks. This comes with the likelihood of more complications, such as bleeding during pregnancy

- Marginal previa: When you have a marginal placenta previa, your placenta is touching your cervix, but it’s not covering it at all

- Low lying placenta: If you’ve been told your placenta is low-lying, it’s just far enough away from the cervix to not be touching or covering it at all

Typically, if you reach week 37 and still have a previa, you will be scheduled for a C-section. In cases of severe vaginal bleeding or other complications, you may deliver even earlier than 37 weeks.

I want to note that there is the possibility of a lateral placenta position wherein your placenta is on either the left or right side of the uterus, but this is the most uncommon position of all!

Complications with the placenta

Placental abruption

View this post on Instagram

Placental abruption is a medical emergency that occurs when part of the placenta detaches from the uterine wall before birth. Most often it occurs in the third trimester, but it can happen any time after week 20. Placental abruptions can be partial or complete, and they’re classified as mild or severe.

Mild abruptions occur when a small part of the placenta detaches. These USUALLY don’t cause serious issues. Severe placental abruptions occur when a big part (or all) of the placenta detaches from the uterine wall.

Mild abruptions (especially prior to 34 weeks gestation) may be treated with hospital or home bed rest and careful monitoring.

For complete or severe abruptions, birth is the best treatment! This can be vaginal if mama and baby are stable, or by emergency C-section, if baby is in distress or mom has lost a lot of blood.

Calcified placenta

As you know, the placenta is the life source of your growing baby, which grows right along with your baby until about weeks 34-36. Once your placenta reaches maturity it often stays stable for a few weeks, and then calcification occurs.

A calcified placenta is when small, round calcium deposits build up and deteriorate your placenta gradually. This is a naturally occurring process and many babies born at full-term have placentas with mild calcification.

Complications can occur when your placenta begins calcifying before week 36 because it might be aging/dying off too quickly to continue sustaining your baby. If your provider thinks baby is at risk due to a calcified placenta you may have an emergency C-section or an induction if you and baby are stable.

Calcified placentas are diagnosed via ultrasound, and in many cases provders find this condition when mamas report a decrease in fetal movement during kick counting.

Placenta accreta

Placenta accreta is a rare, but very high-risk pregnancy complication where your placenta grows too deeply into the uterine wall. In some cases, it actually invades the muscles of the uterus or can grow all the way through it.

This is a high-risk complication because it means that the placenta cannot detach from the uterine wall during the third stage of labor for expulsion.

This puts mamas with placenta accreta at a very high risk for postpartum hemorrhage, and can be associated with premature birth.

You may be at higher risk of developing placenta accreta if you have abnormalities in the lining of your uterus. This might be from a previous C-section or other uterine surgery.

What about umbilical cords?

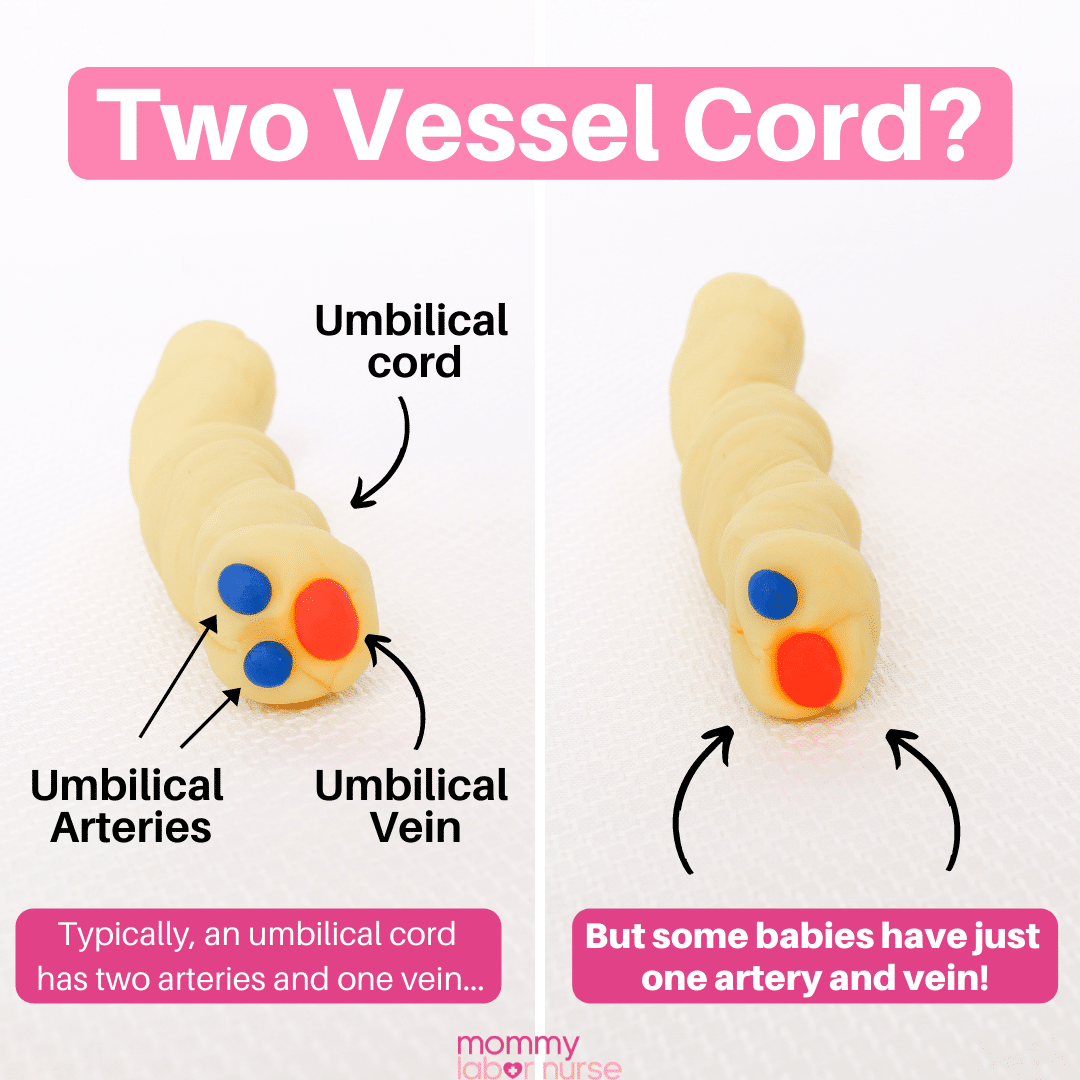

The umbilical cord typically contains two arteries and one vein, which are protected and enclosed by a substance called Wharton’s jelly.

The umbilical vein delivers oxygen and nutrient-rich blood to the fetus, while the arteries return oxygen-poor blood away and back to the placenta for disposal.

The umbilical cord usually attaches in the middle of the placenta and is approximately 50 cm in length. Additionally, there is usually some degree of coiling. That coiling is important because it helps the vessel avoid compression.

If you think about it, something that’s coiled is more difficult to press flat than something that’s not coiled! If your cord is hyper-coiled that can be problematic, too. We really want it somewhere in the middle.

Two vessel cords

As you just learned, a typical umbilical cord contains two arteries and one vein (for a total of 3 vessels!). But there is a complication known as a two-vessel cord where there is only one artery and one vein present.

These are typically diagnosed through ultrasound and are often found at the anatomy scan around 18-20 weeks gestation.

For some women, a two-vessel cord diagnosis doesn’t cause any differences in care at all! Many have healthy pregnancies and deliveries, and extra interventions aren’t needed!

Potential complications of a two vessel cord

However, some babies with a single artery are at increased risk for birth defects such as heart problems, kidney problems, or spinal defects.

Babies with a two-vessel cord may also be at higher risk for not growing properly in-utero. This could include preterm delivery, IUGR (intrauterine growth restriction), or stillbirth.

If your provider detects a two-vessel cord by low-res ultrasound, they may suggest a higher resolution scan to more closely look at baby’s anatomy. Sometimes amniocentesis, fetal echocardiogram, or additional genetic screenings are also recommended.

If your provider doesn’t suspect that baby is experiencing any adverse side effects, they may simply recommend an ultrasound in the future. This may be once per month, or later in your third trimester to ensure baby is growing on track!

Delayed cord clamping

Once baby is born, instead of clamping and cutting the cord right away, you can choose to wait for the cord to be clamped and cut. Standard practice is to wait 60 seconds before clamping the cord.

Most hospitals do this for every baby that is born (unless baby needs immediate medical attention, in which case we would clamp and cut the cord immediately). Some people choose to wait even longer before the cord is cut.

Allowing this extra time before clamping the cord can increase the blood volume in your baby by up to one-third!

This extra blood volume:

- Provides your baby with iron reserves for their first 6-8 months of life

- Improves developmental outcomes in the future

- Increases their hemoglobin and hematocrit levels at birth

- Increases brain myelination

What’s more, is that in preterm babies the benefits of delayed cord clamping are even greater!

Additional benefits for preemies include:

- Improved transitional circulation

- Better establishment of red blood cell volume

- Decreased need for blood transfusion

- Lowered incidence of necrotizing enterocolitis and intraventricular hemorrhage

ACOG notes that there is a small increase in the incidence of jaundice in term babies who delay cord clamping.

Umbilical cord complications

Nuchal cord

View this post on Instagram

A nuchal cord is a medical way of saying that baby’s cord is wrapped around their neck. This is something you’ve probably heard about and you may even know someone who had this happen during their birth. This isn’t at all surprising because nuchal cords are actually quite common – occurring in a little more than 1 in 3 births!

And even though the idea of the cord being wrapped around the neck seems very scary, in reality, the chance of any complications is rare. Sometimes we know about nuchal cords ahead of time because they are seen on ultrasound, but in many cases, we don’t know until baby is born.

The most common complication occurs during labor. Basically, when the cord is wrapped around baby’s neck, it can be compressed during contractions, which in turn reduces the amount of blood (and therefore oxygen) that is getting to baby. Often time, we see a decrease in baby’s heart rate on the fetal monitor, which tells us the cord is being compressed in some way.

True knot

A true knot is when the umbilical cord has a complete and tight knot in it. We consider these a risk to baby because they can cut off blood supply to baby, but we also see healthy babies born with true knots!

Sometimes true knots are spotted on ultrasound before birth, but in many cases, we don’t know one is present until baby comes out!

Umbilical cord prolapse

View this post on Instagram

Cord prolapse is when the umbilical cord drops into the birth canal before baby’s head. In some cases, you can feel it in the birth canal, or it may even stick out of your vagina. This is very dangerous because the cord can easily get compressed and cut off blood flow (oxygen!) to baby.

Cord prolapse happens in around 1 in 300 births, but if it does happen, we need to act quickly to ensure baby’s safety. It can result in brain damage and even fetal death if it’s compressed for too long. If this ever happens to you at home, call 911 immediately!

Typically, the most common cause of cord prolapse is when mama’s water breaks before she’s actually in labor (premature rupture of membranes).

Other risks for cord prolapse include breech baby, multiples, preterm labor, too much amniotic fluid, and prolonged labor. But it can happen in low-risk, full-term pregnancies, too!

So, what do we do if this happens?

We want to get baby out as fast as possible! In the meantime, we’ll have you change positions to get pressure off the cord. Your nurse or OB/midwife will insert two fingers into your vagina (just like a cervical exam) to push baby’s head up slightly, in hopes to relieve the compression put on the cord.

Then, you’ll be rushed to the operating room for an emergency C-section. With prompt intervention, outcomes are usually good!

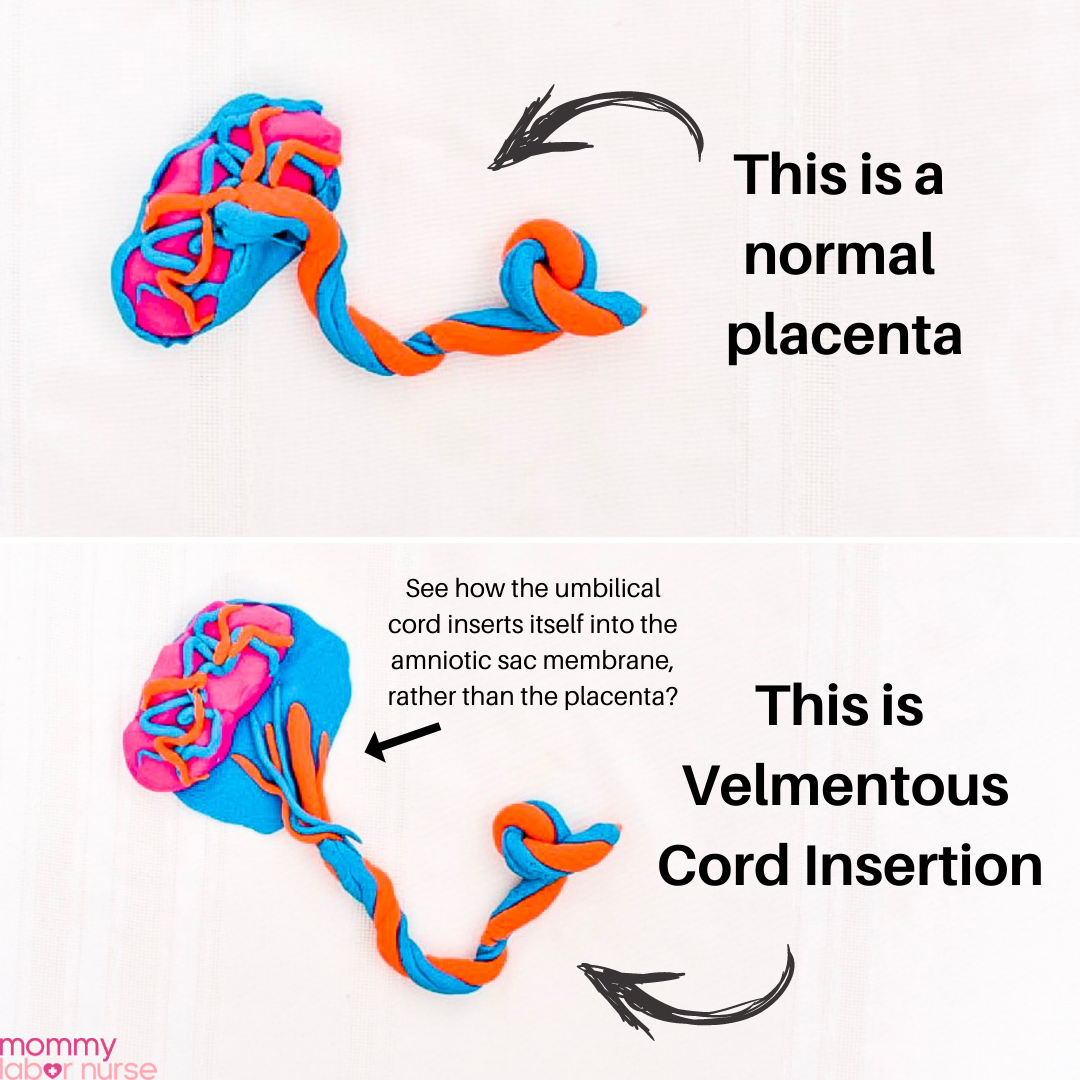

Velamentous cord insertion and vasa previa

Usually, baby’s umbilical cord vessels are attached straight to your placenta. Your bag of water kind of encompasses your placenta from the backside and wraps around the side where baby’s at.

With velamentous cord insertion, the umbilical cord and its vessels are inserted into the bag of water (the fetal membranes) and then travel within the membranes to the placenta.

The exposed vessels are not covered with any Wharton’s jelly (aka the stuff that makes an umbilical cord squishy), so they are more prone to rupture.

Velamentous cord insertion occurs in about 1% of all pregnancies (and a higher likelihood in twin pregnancies). Sometimes it’s apparent on ultrasound before delivery, but sometimes it’s not.

If it’s apparent during your pregnancy, your provider will monitor you closely for the presence of something called vasa previa.

What is vasa previa?

Vasa previa is when those vessels are covering the cervix – you’ll need to have a C-section if that is the case. Many times, women need to have C-sections preterm because vasa previas can be very dangerous if you were to go into labor on your own.

Just because you have velamentous cord insertion does not mean you need a C-section though. As long as baby’s heart rate is stable and you are not having a substantial amount of bleeding during your pregnancy/labor, you can deliver vaginally.

The placenta and the third stage of labor

The third stage of labor is when your placenta leaves your body! After you birth your baby, you’re left with your placenta up in the amniotic sac at the top of your uterine wall.

Once your umbilical cord stops pulsing, and baby’s cord is clamped and cut, your placenta knows it’s time to detach from the inside of your uterus (your body will continue to contract to help with this process!).

Once your placenta detaches, it comes out with the amniotic sac, which was housing baby and placenta!

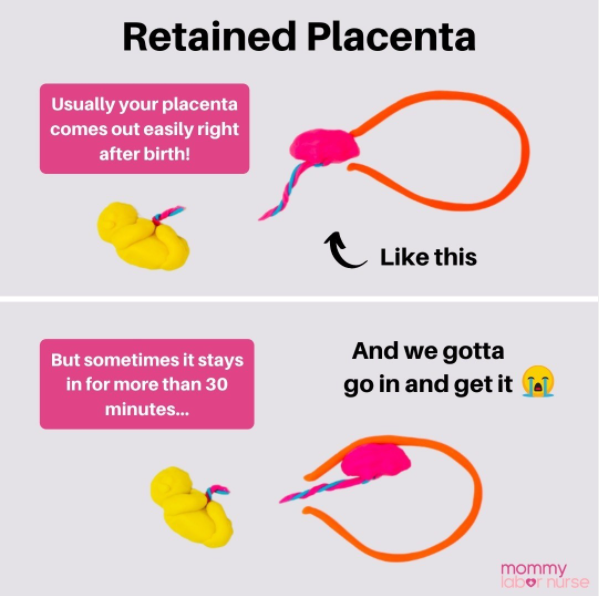

Retained placenta

Most of the time, directly after a vaginal delivery, your placenta comes out on its own. But occasionally, women experience retained placenta. This is when the placenta doesn’t come out for more than 30 minutes (some practices allow for up to 60 minutes).

This can be dangerous for you because you can lose a lot of blood during this time.

In fact, a retained placenta is one of the 4 leading causes of postpartum hemorrhage! If, on the off chance, your placenta is retained there are a few ways of dealing with it.

How retained placenta is treated

Sometimes, your provider can administer medication to try to increase and strengthen contractions to help your body expel your placenta. If this isn’t effective quickly enough, and bleeding is already a concern, your provider may need to reach up into your uterus with a gloved hand and remove your placenta manually.

Occasionally, manually removing the placenta at the bedside doesn’t work. You would need to have a dilation and curettage (D&C) in the operating room when this happens.

Having a retained placenta affects approximately 0.6%-3.3% of women. Your risk increases if you’re experiencing a stillbirth or premature birth.

Very long labors and pushing times also contribute to a slight increase in the risk of having a retained placenta.

Placenta encapsulation

The act of consuming the placenta has been practiced for centuries. However, it is very controversial. 70-80% of moms who choose to consume their placentas choose encapsulation – but it can also be eaten raw (not recommended!), cooked, dehydrated, or roasted.

Placenta encapsulation involves steaming the placenta, drying it out then grinding it up into a powder, and placing it into capsules.

There have been a few studies done on the risks and benefits of placenta encapsulation. However, most of the information we have is anecdotal.

Here are some potential benefits:

- Increased milk supply

- Restoration of blood iron levels

- Increased release of oxytocin, which can help the uterus return to normal size and encourages bonding with baby

- Decrease in postpartum depression

- Increase in corticotropin-releasing hormone, a stress-reducing hormone

Here are some potential risks:

- Placentas can harbor bacteria that can make you and baby sick (if you are breastfeeding)

- Exposure to environmental toxins that accumulate in the placenta during pregnancy

- Lower milk supply – the placenta contains progesterone, which may inhibit the production of prolactin

- Increased risk of blood clots

- Can cause jitteriness and dizziness

If you choose to consume your placenta, make sure it is handled safely by placing it on ice immediately after delivery. It should also be cooked thoroughly before consuming.

There are no laws governing the practice of placenta encapsulation, so it’s important to do adequate research and choose a company that will handle your placenta safely!

The more you know!

Well, mama, there you have it! A deep dive into all things placentas and umbilical cords. It really is true that pregnancy is nothing short of amazing, and understanding the ins and outs of the placenta and cord really speaks to that!

Do you have another question related to placentas or umbilical cords? Shoot me a DM over on Instagram @mommy.labornurse. Maybe you’ll even inspire my next post!